Someone in a zip-up hoodie has just told you that monoliths are architectural heresy. They insist that proper companies, the grown-up ones with rooftop terraces and kombucha taps in the breakroom, build systems the way squirrels store acorns. They describe hundreds of tiny, frantic caches scattered across the forest floor, each with its own API, its own database, and its own emotional baggage.

You stand there nodding along while holding your warm beer, feeling vaguely inadequate. You hide the shameful secret that your application compiles in less time than it takes to brew a coffee. You do not mention that your code lives in a repository that does not require a map and a compass to navigate. Your system runs on something scandalously simple. It is a monolith.

Welcome to the cult of small things. We have been expecting you, and we have prepared a very complicated seat for you.

The insecurity of the monolithic developer

The microservices revolution did not begin with logic. It began with envy. It started with a handful of very successful case studies that functioned less like technical blueprints and more like impossible beauty standards for teenagers.

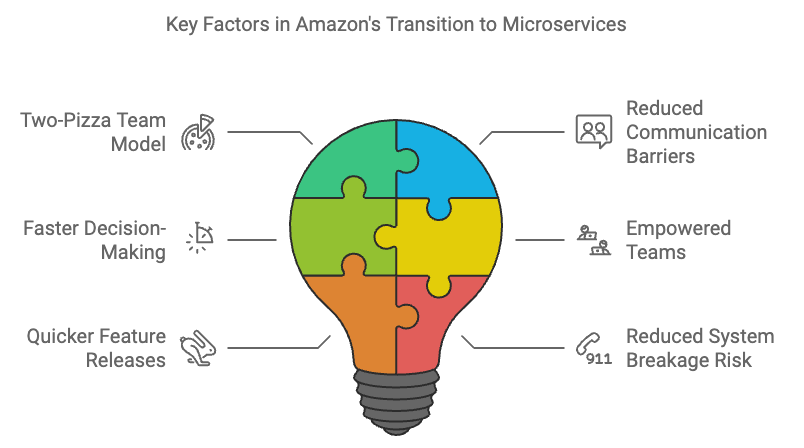

Netflix streams billions of hours of video. Amazon ships everything from electric toothbrushes to tactical uranium (probably) to your door in two days. Their systems are vast, distributed, and miraculous. So the industry did what any rational group of humans would do. We copied their homework without checking if we were taking the same class.

We looked at Amazon’s architecture and decided that our internal employee timesheet application needed the same level of distributed complexity as a global logistics network. This is like buying a Formula 1 pit crew to help you parallel park a Honda Civic. It is technically impressive, sure. But it is also a cry for help.

Suddenly, admitting you maintained a monolith became a confession. Teams began introducing themselves at conferences by stating their number of microservices, the way bodybuilders flex biceps, or suburban dads compare lawn mower horsepower. “We are at 150 microservices,” someone would say, and the crowd would murmur approval. Nobody thought to ask if those services did anything useful. Nobody questioned whether the team spent more time debugging network calls than writing features.

The promise was flexibility. The reality became a different kind of rigidity. We traded the “spaghetti code” of the monolith for something far worse. We built a distributed bowl of spaghetti where the meatballs are hosted on different continents, and the sauce requires a security token to touch the pasta.

Debugging a murder mystery where the body keeps moving

Here is what the brochures and the medium articles do not mention. Debugging a monolith is straightforward. You follow the stack trace like a detective following footprints in the snow.

Debugging a distributed system, however, is less like solving a murder mystery and more like investigating a haunting. The evidence vanishes. The logs are in different time zones. Requests pass through so many services that by the time you find the culprit, you have forgotten the crime.

Everything works perfectly in isolation. This is the great lie of the unit test. Your service A works fine. Your service B works fine. But when you put them together, you get a Rube Goldberg machine that occasionally processes invoices but mostly generates heat and confusion.

To solve this, we invented “observability,” which is a fancy word for hiring a digital private investigator to stalk your own code. You need a service discovery tool. Then, a distributed tracing library. Then a circuit breaker, a bulkhead, a sidecar proxy, a configuration server, and a small shrine to the gods of eventual consistency.

Your developer productivity begins a gentle, heartbreaking decline. A simple feature, such as adding a “middle name” field to a user profile, now requires coordinating three teams, two API version bumps, and a change management ticket that will be reviewed next Thursday. The context switching alone shaves IQ points off your day. You have solved the complexity of the monolith by creating fifty mini monoliths, each with its own deployment pipeline and its own lonely maintainer who has started talking to the linter.

Your infrastructure bill is now a novelty item

There is a financial aspect to this midlife crisis. In the old days, you rented a server. Maybe two. You paid a fixed amount, and the server did the work.

In the microservices era, you are not just paying for the work. You are paying for the coordination of the work. You are paying for the network traffic between the services. You are paying for the serialization and deserialization of data that never leaves your data center. You are paying for the CPU cycles required to run the orchestration tools that manage the containers that hold the services that do the work.

It is an administrative tax. It is like hiring a construction crew where one guy hammers the nail, and twelve other guys stand around with clipboards coordinating the hammering angle, the hammer velocity, and the nail impact assessment strategy.

Amazon Prime Video found this out the hard way. In a move that shocked the industry, they published a case study detailing how they moved from a distributed, serverless architecture back to a monolithic structure for one of their core monitoring services.

The results were not subtle. They reduced their infrastructure costs by 90 percent. That is not a rounding error. That is enough money to buy a private island. Or at least a very nice yacht. They realized that sending video frames back and forth between serverless functions was the digital equivalent of mailing a singular sock to yourself one at a time. It was inefficient, expensive, and silly.

The myth of infinite scalability

Let us talk about that word. Scalability. It gets whispered in architectural reviews like a magic spell. “But will it scale?” someone asks, and suddenly you are drawing boxes and arrows on a whiteboard, each box a little fiefdom with its own database and existential dread.

Here is a secret that might get you kicked out of the hipster coffee shop. Most systems never see the traffic that justifies this complexity. Your boutique e-commerce site for artisanal cat toys does not need to handle Black Friday traffic every Tuesday. It could likely run on a well-provisioned server and a prayer. Using microservices for these workloads is like renting an aircraft hangar to store a bicycle.

Scalability comes in many flavors. You can scale a monolith horizontally behind a load balancer. You can scale specific heavy functions without splitting your entire domain model into atomic particles. Docker and containers gave us consistent deployment environments without requiring a service mesh so complex that it needs its own PhD program to operate.

The infinite scalability argument assumes you will be the next Google. Statistically, you will not. And even if you are, you can refactor later. It is much easier to slice up a monolith than it is to glue together a shattered vase.

Making peace with the boring choice

So what is the alternative? Must we return to the bad old days of unmaintainable codeballs?

No. The alternative is the modular monolith. This sounds like an oxymoron, but it functions like a dream. It is the architectural equivalent of a sensible sedan. It is not flashy. It will not make people jealous at traffic lights. But it starts every morning, it carries all your groceries, and it does not require a specialized mechanic flown in from Italy to change the oil.

You separate concerns inside the same codebase. You make your boundaries clear. You enforce modularity with code structure rather than network latency. When a module truly needs to scale differently, or a team truly needs autonomy, you extract it. You do this not because a conference speaker told you to, but because your profiler and your sprint retrospectives are screaming it.

Your architecture should match your team size. Three engineers do not need a service per person. They need a codebase they can understand without opening seventeen browser tabs. There is no shame in this. The shame is in building a distributed system so brittle that every deploy feels like defusing a bomb in an action movie, but without the cool soundtrack.

Epilogue

Architectural patterns are like diet fads. They come in waves, each promising total transformation. One decade, it is all about small meals, the next it is intermittent fasting, the next it is eating only raw meat like a caveman.

The truth is boring and unmarketable. Balance works. Microservices have their place. They are essential for organizations with thousands of developers who need to work in parallel without stepping on each other’s toes. They are great for systems that genuinely have distinct, isolated scaling needs.

For everything else, simplicity remains the ultimate sophistication. It is also the ultimate sanity preserver.

Next time someone tells you monoliths are dead, ask them how many incident response meetings they attended this week. The answer might be all the architecture review you need.

(Footnote: If they answer “zero,” they are either lying, or their pager duty alerts are currently stuck in a dead letter queue somewhere between Service A and Service B.)